indicator

Calligraphy – the art of writing

A cherished Korean art form that conveys the artists' emotions while illustrating the strength, purity and perpetuity of this ancient tradition.

<The practice of calligraphy with the "four friends": paper, brush, ink stick, and ink stone.>

Characters become art

In Asia, the act of giving a work of calligraphy created by one's hand to someone symbolizes the great respect the artist has for that individual, and is considered a true gift of the heart. This is because in Asian cultures, calligraphy is not merely a technical exercise in handwriting, but an act of training and disciplining the mind. Eastern calligraphy, a visual art form in which writing is designed and executed with a brush, is distinct from its Western counterpart. While Western calligraphy also regards letters as objects of aesthetic beauty, Western calligraphy focuses more on forming letters on paper in a clear and beautiful way—a purely artistic endeavor—while the calligraphy of various Eastern countries including Korea is a meaningful, exquisite art form that utilizes the shapes and meanings of characters to express the calligrapher's emotions. This is why all Asian calligraphic works clearly reveal the personalities of the artists who created them. And with the long years of practice needed to perfect this art form, calligraphy in Asia is so much more than just a technical exercise—it is a form of mental training, the reason why it is called "the way of the word."

<Participants wearing traditional Korean Hanbok are writing answers in a re-enactment of the state examination from the Joseon Dynasty.>

The "four friends" of every calligraphic practice: paper, brush, ink stick, ink stone

There are four main tools that are required for the practice of calligraphy—paper, brush, ink stick, and ink stone. These "four friends," or "Munbangsawoo" in Korean, were commonly found objects in the studies of pre-modern Korean homes. The paper for calligraphy must be traditional hanji (Korean mulberry paper), which is particularly well-suited for absorbing ink and reflecting its colors, while the brush must be straight and have a sharply-pointed tip made of animal hairs of the same length. After being used, the brush must be washed clean before being stored. The ink stick is made by mixing soot from burned trees and glue. The particles of a good ink stick are extremely fine and firm. The ink stone onto which the ink stick is ground must be made from a firm stone that does not absorb water, or jade. In addition to these four tools, several other items are needed for calligraphy, including the yeonjeok (a container for holding the water needed to grind the ink stone), boot tong (a container for holding brushes), munjin (long and flat paperweights), and pilse (a bowl for washing the brush).

<Munbangsawoo from the Joseon Dynasty on display at the Busan Museum.>

Calligraphy: enjoyed with the eyes and engraved onto the heart

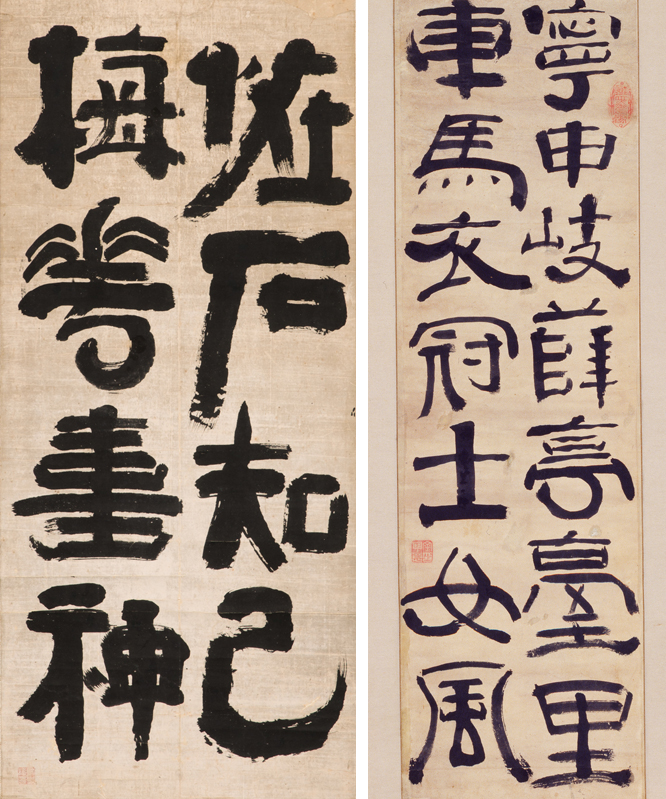

Calligraphy expresses the structural beauty of Chinese (or Korean) characters with a brush and black ink on a white page. The aesthetics of each calligraphic work depend on its composition: for example, the balance and proportion of dots and lines—large or small, long or short—and the positioning of empty space. Also, depending on the rhythm and flow of the writing—strong or weak, fast or slow—the beauty of movement is created. It is this movement and the various shades of black that result from it that express the calligrapher's mood. All of these aspects combined—the aesthetic of space created by the ink's color, the positioning of the characters, and the magnificence of movement of the written characters—allow the personality of the calligrapher to shine through the work. Calligraphy artists usually express classic citations or well-wishing sentences in their pieces, and in the process of creation engrave the words not only on the paper but into their hearts.

<Calligraphy works by Kim Jeong Hui (1786-1856), a calligrapher during the Joseon Dynasty considered to be the finest in Korean history.>

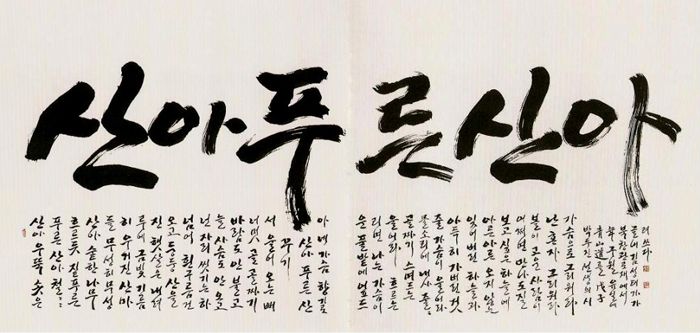

The simple but strong beauty of Hangeul calligraphy

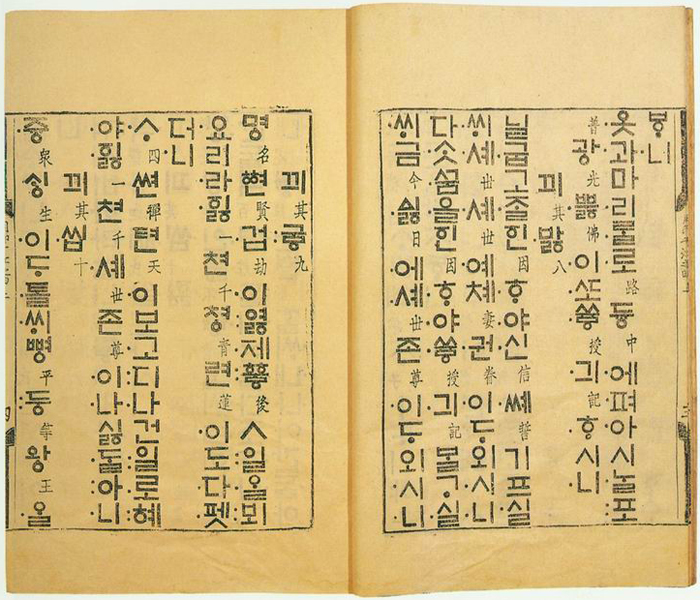

Contrary to Chinese character calligraphy, which possesses a variety of fonts developed over several millennia, Hangeul (Korean) calligraphy is only about 500 years old. Despite its relatively short history, Hangeul calligraphy is beloved by many calligraphy enthusiasts for its simple and restrained beauty, and unexpected strength. Hangeul calligraphy is constantly being developed, with increasingly more attempts to create new fonts and writing styles. There are many places in Korea that offer calligraphy classes for foreigners, including Namsan Hanok Village. Such classes are open to all those who have an interest in learning calligraphy; in fact, they are widely enjoyed by members of foreign embassies and companies operating in Korea. There are also a variety of calligraphy competitions especially for foreigners held each year.

<The first printed copy of a song composed by King Sejong the Great, the inventor of Hangeul.>

<A calligraphic work by modern calligraphy artist Kim Sung-tae. It reads, "Mountain, blue mountain," a line from the poem Cheongsando by Park Du Sin.>

<A woman tries calligraphy on a visit to Korea.>

* Photos courtesy of Korea Tourism Organization and Cultural Heritage Administration of Korea.